If you think of visiting Japan, it is worthwhile to include a temple stay in your plans. A temple stay is easily organised, but you’ll have to remember to reserve it in advance, especially if you are visiting during the high season. Many temples are popular pilgrimage destinations, and as such, their lodgings tend to fill up quickly.

One of the most popular towns to experience a temple stay is Koyasan. The small town has got more than 50 temples and because of its popularity, monks are used to receiving foreign visitors and speak good English. Prices vary greatly depending on the season and on the temple. For a rough idea, you can pay from 70 to 200 EUR per night, per person (with dinner and breakfast included).

What to expect from a Buddhist temple stay?

Our plan was to stay in a Buddhist temple in Koyasan to get a taste of the lifestyle of Japanese Buddhist monks. Some temples allow visitors to participate in the meditation sessions led by the monks, as well as in the morning prayers. We headed to one such temple. But when we arrived there, we were greeted with the bad news that they only had one room available and that it would cost us 400 EUR for one night. The young monk could see the disappointment in our faces and to our surprise told us that, if we didn’t find any other alternative, we could stay with him at his place.

After that kind invitation, we didn’t even feel like searching for an alternative. If we wanted to know the real lifestyle of a monk, there was no better way than having a private stay, away from any tourist might-be traps. Nevertheless, we went to the tourist office, realised there were no vacancies anywhere and accepted the kind monk’s invitation.

The Secret Life of a Buddhist Monk

Given the intimate content of this account, we will not disclose the real name of the monk who invited us. Instead, we will call him Kao.

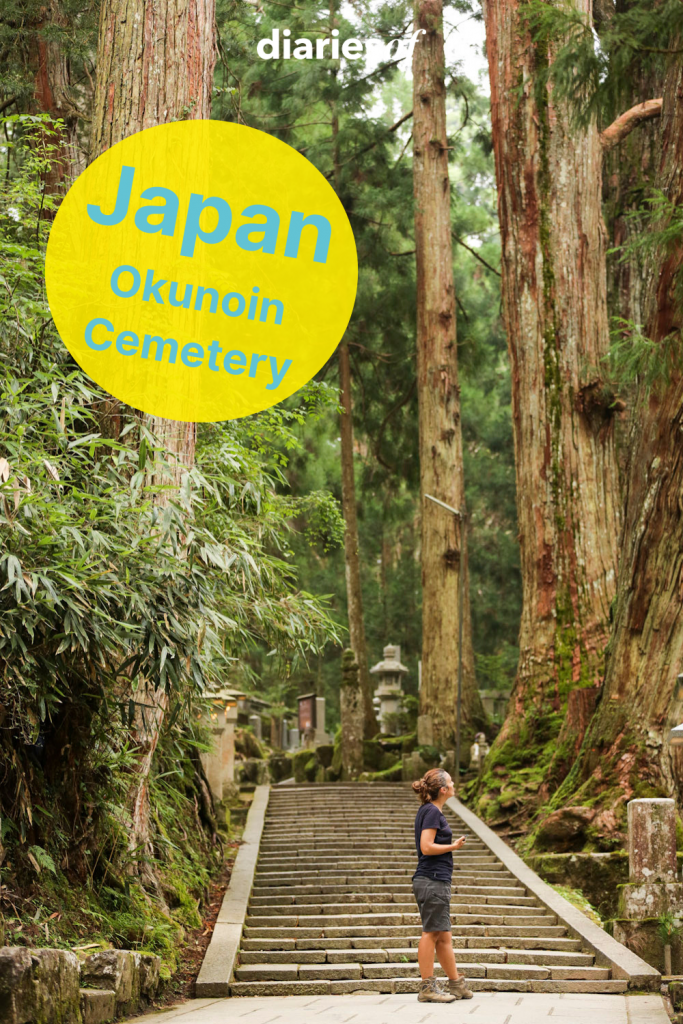

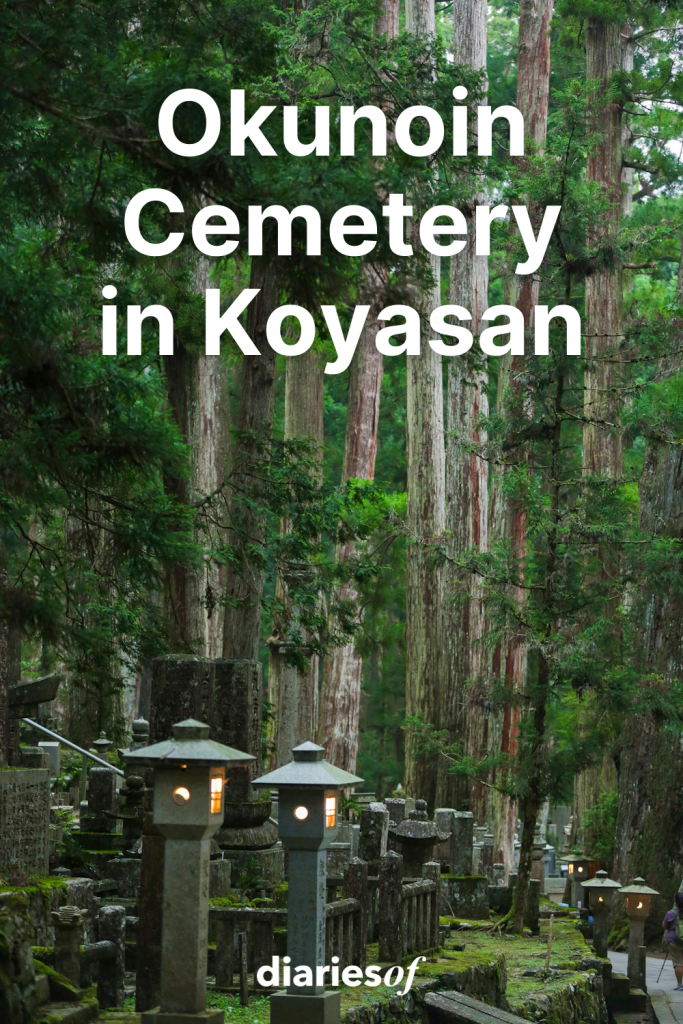

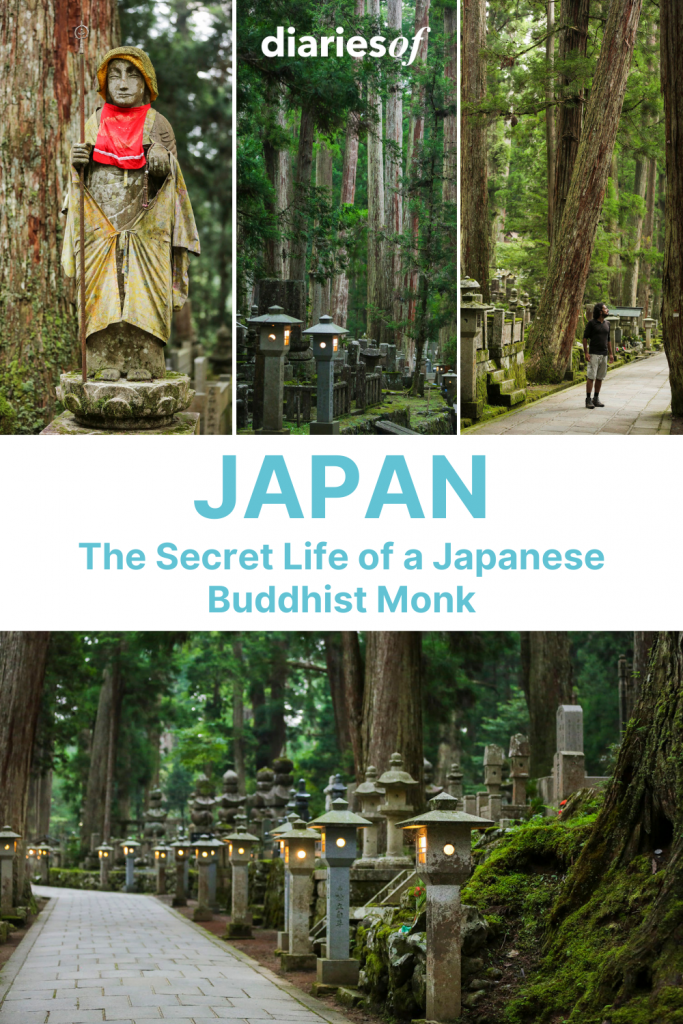

We would meet Kao later in the evening. Before that, we had time to stroll through town, and more importantly, to visit the Okuno-in cemetery. In this cemetery, there are more than 200,000 tombs, spread throughout an immense cedar forest. This is probably the most beautiful and atmospheric cemetery we have ever been to.

We walked the path that took us for two mystic kilometres through tombs, stones and trees, all covered in moss, reminding us that this is a very humid place. In the end of the path stands the main temple and main tomb of the cemetery, where the founder of Shingon Buddhism is buried.

We met Kao at the temple after his shift. From there we would drive together to his apartment, but before that, we took a bath at the temple. Jorge followed him to the gens’ public bathhouse, while I was shown the ladies’. Kao offered me a towel and we made an appointment to meet after the bath, 30 minutes later.

I was alone at the women’s public bath. By now I knew already how to behave in a public bath, and sat on one of the small plastic stools in front of a mirror, scrubbing myself with the small towel that Kao had handed me. When all my body was well rubbed, I stepped into the hot-water sink, where I had at least another twenty minutes to relax and swelter. Time to appreciate the slow rhythm of life in the temple.

Kao drove – for Japanese standards – like crazy. His tiny Suzuki swirled along the streets of Koyasan, as if we were late to an important appointment. So much for all the relaxing time in the pool! The first surprise when we arrived at his place, was that the house wasn’t locked. Kao simply slid the entrance door without using any keys. We had already noticed that Japan was a very safe country, but we were not aware it was THAT safe and that people still did not feel the need to lock their homes.

We sat on the tatami while Kao fetched some drinks downstairs from the kitchen. Monks are given the choice of where to live: in the monastery or on their own. Kao chose to live in a flat on his own. After finishing his studies in economy, Kao worked in the import/export industry. From there he moved to Australia to improve his English while working in the harvest of melons and fishing crabs. After Australia, he moved to India for a 12 days meditation retreat. In India, he realised that people there lived with very little but somehow were happy; it was the opposite of Japan, where people had everything but felt unhappy, he said. It was also in India that he came across different drugs and even tried a few. After this introduction, Kao stood up to get a small box, from where he got tobacco and weed. He rolled a joint. ‘In Japan, we are not allowed to smoke weed, but as long as we remain discreet that’s ok’, he said while puffing his blunt.

Kao has been working in this monastery for one year and a half and became a monk six months ago. He explained that even though he is a monk, he is free to marry if he wants to and he is also free to abandon his role as a monk whenever he wants to. It is quite usual that Buddhist devotees become monks for a period in their lives only, and then return to ‘normal’ life outside the monastery.

The temples from the Shingon esoteric Buddhism are exploited by private families. The eldest son of the family knows that he will inherit the temple. In order to run it, he needs to become a monk. In these cases, these monks don’t have the freedom to renounce being a monk. If they do, they can’t run the family business. As Kao explained this, it became clear to us why it was so expensive to stay in a temple. Temple stays are afterall a business and an important income stream for monasteries.

During his studies, Kao was already interested in religion. His Ph.D. thesis was about the relationship between economics versus religious beliefs. He defended then that money replaces faith. Taking in consideration the exorbitant prices that monasteries were applying, we thought he was absolutely right.

It was already late when Kao prepared a futon for us, on the tatami floor of the room next to his. We slept very comfortably until the next morning, when it was time for us to leave. Kao had left earlier to join the morning prayers at 6 am, and we met him afterwards, outside the temple to say good-bye. He had made two lucky amulets for us. ‘They are Buddhist lucky charms that I made myself. They will protect you on your journey against any harm.’ We were touched by his gesture and kept those amulets with us, in our bike, throughout our journey in Japan…

Pin For Later

Click one of the images to save it on your Pinterest

2 Comments